Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

J Sustain Res. 2026;8(1):e260009. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20260009

1 Centre for Educational Research, School of Education, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia

2 Australia World Leisure Centre for Excellence, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia

* Correspondence: Tonia Gray

This mixed-methods research examined the impact of the Guardians of the Park program, a 10-week nature-based intervention supporting adolescents experiencing social and educational disadvantage in Western Sydney. Grounded in biophilia theory and utilising a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, the study explored whether immersive habitat restoration, cultural learning, and outdoor education could strengthen nature connectedness, self-esteem, and social-emotional wellbeing. Quantitative data were collected using the Extended Inclusion of Nature in Self (EINS) scale, complemented by qualitative data from observations, interviews, and reflective field notes. Due to irregular attendance and literacy challenges, qualitative data emerged as the most reliable indicator of student experience and change.

Findings demonstrated notable improvements in social skills, confidence, autonomy, and executive functioning. Participants showed strengthened peer relationships, increased willingness to take on leadership roles, and greater emotional regulation. A deepening attunement to place emerged as students became more observant, appreciative, and respectful of the natural environment. Cultural engagement with First Nations educators proved particularly influential, fostering belonging, curiosity, and connection to Country. The program structure, flexible, relational, experiential, and strengths-based, was found to support its effectiveness.

From these findings, a set of provisional design principles were analytically derived, highlight the importance of cultural grounding, reflective practice, intergenerational connection, and participatory program structures. The study suggests that structured nature-based programs may support pro-social behaviour, wellbeing, and ecological connection among disengaged youth, offering insights to inform future research and contextually responsive practice across education, public health, and community initiatives. A longer-term project implementation phase will extend through 2028 to refine tools and measure sustained effects.

Nature connectedness has attracted growing attention as researchers recognise its vital role in both planetary and human wellbeing. Strong relationships with the natural world foster pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours while enhancing psychological health and cognitive performance. A substantial body of research has shown that engagement with nature improves mood, alleviates symptoms of anxiety and depression, and supports overall wellbeing [1–5]. Strengthening human-nature relationships, therefore, is both a pathway to personal wellbeing and a foundation for ecological stewardship.

Developing nature connectedness is fundamental to education for sustainability, as it nurtures ecological empathy and a sense of shared responsibility for the living world. When people feel emotionally linked to a place, they are more inclined to value and protect it. As Tuan [6] suggests, a place becomes truly real when experienced through multiple senses. Outdoor educational experiences engage the whole body and mind, cultivating sensory, emotional, and reflective relationships with the natural environment.

Adolescent Disconnection from Nature in Urban ContextsNature connectedness is a multidimensional psychological construct encompassing cognitive, emotional, and behavioural components [7]. It is influenced by gender, age, culture, socioeconomic context, and the quality of experiences in nature [8]. While extensive research highlights the wellbeing benefits of sustained nature connection, relatively few studies examine the growing disconnection from nature experienced by adolescents, especially those living in disadvantaged urban environments.

Empirical evidence indicates a marked decline in nature connectedness during adolescence [9–12]. Many young people now engage primarily in sedentary digital activities, such as gaming and social networking, rather than outdoor play or exploration [8,13]. This disengagement is particularly concerning in socioeconomically disadvantaged urban areas where access to quality green space is limited [14–16]. Reduced exposure to nature correlates with heightened risks of anxiety, depression, and behavioural challenges in children and adolescents [3,17]. Supporting our young people to feel connected with the natural world is imperative for both human and planetary health.

The Equigenic Effect of GreenspaceThe transformative role of green environments in mitigating health inequalities is encapsulated in the equigenesis hypothesis of greenspace or equigenic effect [18]. This theory proposes that exposure to natural settings can reduce health disparities, particularly among economically disadvantaged populations. The equigenic effect reflects how equitable access to healthy ecosystems supports both social and ecological wellbeing. By improving the quality and availability of natural environments, communities can foster more just, resilient, and sustainable urban systems [16,19].

Mitchell, Richardson [20] reported that access to green space can reduce socioeconomic disparities in mental wellbeing outcomes by as much as 40 percent. Similarly, Kuo and Sullivan [21] found that residents of buildings surrounded by greenery reported lower aggression and violence than those in barren settings, outcomes attributed to improved attention and reduced mental fatigue. These findings highlight how access to restorative green spaces not only promotes health equity but also cultivates the conditions for social cohesion—an essential dimension of sustainable community design.

Despite promising evidence, research on the equigenic effect remains mixed. Variations in how “greenspace” is defined and measured complicate cross-study comparisons. Wang, Feng [16] addressed this gap by analysing high-resolution “street-view” data in China to explore relationships between greenspace characteristics and mental health among low-income populations. Results indicated that both greenspace quality and quantity play significant roles in narrowing mental health inequalities. Such evidence underscores the importance of embedding environmental justice and nature-connected learning within sustainability education, ensuring that every young person, regardless of socioeconomic context, can experience the wellbeing and empowerment derived from meaningful contact with the natural world.

Technology, the Adolescent Brain, and Nature ConnectionThe pervasive presence of digital technology exerts a profound influence on adolescents’ connection to nature [13,22]. While digital environments offer social and educational benefits, their long-term effects on the developing brain are still poorly understood. Extended screen time has been linked to changes in attention, emotional regulation, and sensory processing pathways [23]. As adolescents spend increasing hours in virtual spaces, their embodied engagement with the physical world may diminish, potentially reshaping their environmental identity.

Relph [24] contends that digital technologies have altered our perception of place, producing a form of digital disorientation that erodes spatial awareness and attachment. Evidence suggests this may also distort young people’s ecological understanding, for examples, students have become more familiar with and concerned for exotic species, such as pandas and polar bears, than local endangered species [8,25]. This pattern likely reflects limited direct engagement with nearby nature, which weakens bioregional knowledge and appreciation of local biodiversity.

Measuring Connection to Nature for Sustainability EducationUnderstanding how adolescents relate to nature enables educators to design targeted programs that foster environmental stewardship and wellbeing. Numerous instruments have been developed to measure nature connectedness and its links to cognitive and emotional outcomes. Among the most widely used are the Nature Relatedness Scale [26], the Connectedness to Nature Scale [27], and the Inclusion of Nature in Self (INS) scale [7]. Across these measures, higher nature connectedness is associated with greater emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility, and pro-environmental behaviour.

The INS scale is particularly practical for use with children and adolescents due to its simplicity and visual format. It measures perceived overlap between self and nature, reflecting how strongly individuals identify with the natural world. To improve the scale’s psychometric reliability, Martin and Czellar [28] developed the EINS scale, a four-item tool using spatial metaphors to capture self-nature overlap. Its accessibility makes it valuable in environmental education contexts, especially for younger participants, those with limited literacy, or people with cognitive disabilities.

By enabling educators to assess changes in students’ environmental identity, such tools inform program design and evaluation in sustainability education. They also bridge psychological and pedagogical perspectives, reinforcing the idea that cultivating emotional and cognitive bonds with nature is integral to transformative learning for sustainability.

Restoring Connection through Place-Responsive PedagogySubstantial evidence links time spent in nature to both wellbeing and pro-environmental attitudes [26,29,30]. The United Nations’ Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) framework [31] advocates for community- and school-based programs that simultaneously enhance planetary wellbeing and human connectedness to nature. Outdoor and environmental education programs are consistently associated with stronger nature connection and environmentally responsible behaviours [8,32,33]. Such experiences also shape place-identity or how individuals perceive themselves in relation to their environment [34]. Tracey, Gray [35] found that well-designed environmental education initiatives enhance emotional resilience, reduce anxiety and depression, and improve social cohesion.

For adolescents in disadvantaged urban contexts, nature-based interventions represent not only a wellbeing strategy but also a form of social and environmental justice. Place-based programs reconnect youth with local ecosystems, strengthen community resilience, and nurture the pro-environmental dispositions necessary for a sustainable future.

This paper analyses a 10-week immersive habitat restoration program for disadvantaged youth living in Western Sydney. The use of the term ‘disadvantaged youth’ refers to youth from low socio-economic backgrounds in the lower quartile of household income. Greater Sydney Parklands (GSP) is the NSW Government agency responsible for more than 6000 hectares of urban green space across Sydney, including Centennial Parklands, Western Sydney Parklands, Parramatta Park, Callan Park, and Fernhill Estate. Through its Education and Community Programs, GSP connects tens of thousands of people each year with nature, culture, and community, focusing on wellbeing, inclusion, stewardship, and lifelong learning. GSP initiatives engage children, young people, and schools in place-based experiences that build environmental awareness, social connection, and a sense of belonging.

The Guardians of the Park (GoP) program was established in response to a series of arson incidents within the parklands as a collaborative initiative between GSP, the NSW Police Youth Liaison, the Rural Fire Service, and First Nations education providers. The initial cohort consisted of young people directly involved in lighting fires, and the program was designed as a non-punitive response combining environmental education, practical conservation work, cultural learning, and positive engagement in outdoor settings. Over time, the GoP evolved beyond this focus and is now offered more broadly to adolescents aged 14 to 17 who are disengaged from or disadvantaged in mainstream schooling, particularly those who benefit from experiential, nature-based learning environments, rather than traditional classrooms.

The program is facilitated by experienced GSP educators trained in inclusive and responsive practice, working alongside schools and First Nations knowledge holders. Activities are designed to be sensory-aware and place-based, maximising group cooperation and nature connection opportunities to develop social skills, emotional regulation, confidence and environmental responsibility. From its inception, the GoP has incorporated principles of participatory and nature-based pedagogy, with participants helping shape the direction and focus of program activities. This co-creative approach strengthens engagement, fosters agency, and deepens connection to place [35]. To this end, the program structure was refined in its first year, reducing group sizes from 20 to 10 to create space for deeper relationships, tailored activities and responsive facilitation. The program continues to be reviewed and adapted to reflect participant needs and emerging best practice.

ParticipantsCohorts attend the program with their regular teachers and School Learning Support Officers (SLSOs), with coordinating teachers selecting participants for whom conventional classroom approaches have proven ineffective. A significant proportion present with complex cognitive, behavioural and sensory profiles, including, but not limited, to neurodivergent diagnoses such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). ADHD is characterised by difficulty with attention regulation, planning, and impulse control, whilst individuals with ASD experience atypical social communication and sensory processing [36,37]. For the program’s demographic, anxiety and other emotional regulation challenges are also frequent [38]. Participant needs are supported by embedded frameworks such as carefully sequenced activities, predictable routines and environmental adaptations, as well as concrete supports that include social stories and visual schedules.

Many participants also come from low socio-economic backgrounds and complex family circumstances. Cohorts reflect a wide diversity of nationalities, languages, and cultural identities. Many participants are first- or second-generation Australians, whilst there are also First Nations students within many groups. This diversity, in combination with the prevalence and diversity of additional needs, underscores the program’s role as a flexible and inclusive intervention for young people who face significant barriers to participation.

The GoP reflects GSP’s broader commitment to using public parklands as places of growth, learning, and connection for those excluded by conventional educational settings. During the program, students learn and practice hands-on land management practices, including Indigenous land management techniques and bush survival skills, whilst restoring 3000 sqm of bushland and planting 4620 native trees [39]. After the completion of the course, students were invited to return as mentors for future sessions. The program is multidimensional in its aims—focusing on supporting disadvantage youth to reengage with their education, strengthen students’ relationship to the environment, and regenerating the environment itself. Specifically, the program was designed to enhance students’ sense of place and belonging, improve levels of self-esteem and increased students’ overall wellbeing. Environmentally, the program also aims to restore threatened habitat in Western Sydney Parklands and increase the park’s resistance to climate change, however, reporting on the environmental outcomes is beyond the scope of this paper.

Ethics approval for a mixed-methods research study was granted by Western Sydney University [H15538]. The study investigated the impact of the GoP program on disadvantaged youth in Western Sydney and aimed to:

●

●

●

●

A mixed-method research methodology was employed in the quest to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between place attachment and well-being in disadvantaged youth. The design incorporated both qualitative and quantitative methods to comprehensively evaluate changes in participants’ connection to place, self-esteem, and overall wellbeing. Quantitative data was gathered through the application of the EINS scale at the beginning (pre-test) and end (post-test) of the program. This scale explores participants’ perception of their relationship to place and environment through the use of spatial metaphors (see Appendix 1).

The EINS scale, developed by Martin and Czellar [28] and adapted from Schultz [7] INS scale, was chosen for its simplicity, visual approach, and suitability for the program. The scale is a self-report measure, which minimises the need for extensive reading or writing, therefore making it accessible to a diverse range of participants. For rigour, the scale was triangulated with qualitative data collected from field notes and recorded reflections. The GoP staff were trained in delivering the survey and asked to administer it at the end of the first and last session.

The epistemological framework emphasised the subjective experiences of participants and educators. As Smith and Osborn [40] write the challenge is for the researchers to reliably and valuably capture the participant’s experience. Haraway [41] discusses how in traditional Western notions of objectivity the researcher is absent—“seeing everything from nowhere”. This paper pushes back against this epistemological framing and make interpretations visible through using field notes.

Yu [42] emphasises the need for flexibility, particularly pertaining to ethnographic fieldwork, as ‘the relationship between in-place and out-of-place is neither linear nor binary’. Similarly, McArdle [43] posits that a flexible methodological approach ‘allows researchers to be open and adaptable to changes within the research’ and follow emergency narratives ‘rather than being pre-constrained by rigid frameworks’. Given the evolving and situated nature of working with adolescents in a dynamic, outdoor program the methodology incorporated an adaptable, developmentally-appropriate approach. Researchers were flexible with their roles and data collection methods and responsive to emerging situations and group temporalities. At times, the researchers were directly involved in guiding activities; at other moments, they adopted the roles of observer, stepping back to allow the natural and authentic group dynamics to unfold.

Data collection methods emphasised natural conversations and the spontaneity of interactions, rather than prescribed and formal time-constrained interviews. Interviews and reflections were incorporated organically into the program, lasting anywhere between 30 s and 5 minutes, enabling participants to share their experiences in natural and unforced ways. Flexible interview scaffolds also allowed the researchers to respond creatively to opportunities for deeper insight; for example, sometimes when doing activities such as planting trees or weeding, short interviews were conducted. These unstructured moments were intentionally incorporated to stay true to the participants’ experiences and the program’s ecological context. Moreover, avoiding formalised data collection techniques minimised inherent power dynamics that may lead participants to specific answers or the belief that there may be a correct answer. As Bolzan and Gale [44] argue, standard interviewing processes risk ‘basically reinforcing sociological realities rather than eliciting the young people’s social reality’.

All interviews were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed. The data underwent a detailed thematic analysis that aspired to reflect the participants’ experiences. Thematic analysis was selected for its coherence, flexibility, and applicability in analysing qualitative data, particularly that which has been developed through a phenomenological lens [45]. In conjunction with a phenomenological lens, thematic analysis created a synergy whereby reoccurring themes were identified, and the participants’ experiences were accentuated. For example, thematic analysis captures reoccurring patterns while understanding phenomena through the lived experience. The qualitative data analysis software NVivo (version 1.6.2, Lumivero, Denver, USA) was used to organise the codes electronically. Data collection has spanned 12 months and involves four cohorts of roughly 6–12 participants each. Parental or guardian consent was required for all participants involved in the research. Acronyms have been used to protect the identity of the participants, and any revealing information has been redacted.

Findings have been organised into the key themes that arose from the thematic analysis. To ensure a logical flow and continuity, data has not been separated according to students, educators, and facilitators involved in the GoP program. There were similar themes that arose from all three participant groups, making it more cohesive to present the data together. The data illustrates the transformative and wide-ranging impacts of the program. The key themes include: social skills and confidence; autonomy and executive function; behavioural changes; ripple effects beyond the program; attunement and sense of place; teamwork and collaboration; and skill development and enjoyment.

Social Skills and ConfidenceA key theme emerging from the analysis was the growth of students’ social skills and confidence. Educators and facilitators consistently observed notable shifts in students’ attitudes and interactions over the course of the program. One educator described how students on the Autism spectrum became more comfortable and engaged socially:

You know, by coming out to Bungarribee with a group of his peers, he definitely became more sociable. His social skills and reasoning increased dramatically.

The educator continued, describing another student:

So [name redacted] over there with the hat… he has become much more sociable. So now these are his group of peers, but even last session when he was the only one in his year group, he became sociable with the boys above his grade.

Findings suggest the program fostered new forms of social connection and inclusion. Students mentioned how the experience of working together outdoors built trust and reduced social anxiety. A teacher noted:

I think the biggest observation for me was just watching the students’ confidence grow being out here.

Educators observed increased student engagement and leadership. One teacher reflected:

[Name redacted], he’s the oldest student. He, before this, didn’t talk, rarely opened his mouth. Now, after his second year, or second time through, he’s leading, he’s learning.

Educators perceived that the program encouraged collaboration across peer groups who would not typically mix at school.

So, [name redacted] only hangs out with like the sporty kids [at school]. He wouldn’t hang out with these kids but now we’re seeing them work together. [educator]

Students frequently mentioned teamwork as one of their favourite aspects of the program:

I liked working in a group. [student]

Teamwork and learning about the different weeds. [student]

I would say definitely working as a team, finding new weeds to pull out and being together in nature is really nice. [student]

We get do activities with friends. [student]

Teamwork was also evident to educators:

You know, I will be like, ‘I don’t reckon we can get those plants in the ground’. And then, obviously, the students take that, you know, to heart, and they’re like, no, no, we can. And so, they smash it out, and then we end up pulling ridiculous numbers like we did with the weeding.

Participants described the program’s capacity to build cooperation, belonging, and pride through collective environmental action. By grounding teamwork and connection in shared ecological tasks, the program cultivated both interpersonal and environmental responsibility.

The findings of positive social outcomes carry implications for youth wellbeing. The Headspace [46] National Youth Mental Health Survey reported that 60% of young people aged 12–25 feel lonely or left out. Loneliness has been linked to poorer health outcomes, including depression, substance misuse, and even elevated risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood [47,48]. Participants’ strengthened confidence and social bonds act as protective factors against loneliness and isolation [49]. By reweaving social relationships through shared outdoor learning, GoP offers an example of sustainability education in action, nurturing community wellbeing alongside ecological restoration.

Agency and Participatory Learning

A defining feature of the GoP program was the autonomy it offered students. Activities that allowed for independence and choice were consistently rated as favourites, giving participants a sense of control and ownership over their learning.

I liked the exploring. The exploring and the adventure. [student]

Students valued opportunities to use real tools and practice practical bush skills:

I’m grateful that I got chosen for this. I’ve learnt how to cut down a tree, how to safely make a fire and planting.

Facilitators observed a strong willingness to engage deeply with these experiences and to take initiative:

So, I think [name] was one of the hardest workers I had when we planted the native garden. She just took initiative, she’s always happy to learn.

Interview findings suggest the program positioned students as active participants in their own learning, an essential principle of sustainability education, where agency and experiential engagement underpin transformative learning.

Bolzan and Gale [44] describe such environments as interrupted spaces—contexts where the usual rules and hierarchies governing young people’s lives are temporarily suspended. Within these spaces, marginalised youth can “explore new ways of being and have their perspectives sought and respected by adults”. The GoP created this kind of space by offering real responsibility, trust, and responsiveness to student curiosity.

A clear example occurred when a student initiated a discussion on water filtration. Rather than redirecting the student back to the task at hand, facilitators embraced the topic, later organising a workshop for students to test different filtration methods using water from the river. This responsiveness reversed typical power dynamics between adults and young people, positioning students as knowledge holders and co-designers of their learning.

Interviewer: So, do you like to come out here?

Student: Yeah, definitely.

Interviewer: Why’s that?

Student: When else do I get to do this? They don’t allow anyone to go into a park and cut trees and have a fire.

For many participants, this freedom acted as a circuit breaker and interrupted patterns of social control and disengagement common in their everyday environments. The program thus became an interrupted space where new relationships with adults, peers, and place could emerge [44].

By empowering students to make decisions, take risks, and learn through direct interaction with the natural world, the program embodied the principles of participatory and sustainability-oriented pedagogy. Students developed executive functioning, self-efficacy, and environmental agency. These capacities are essential not only for personal growth but for cultivating future citizens capable of contributing to sustainable communities.

Ecological Attunement and Sense of PlaceDeveloping a sense of place and deepening connection to the landscape at Western Sydney Parklands were central aims of the GoP. Students’ reflections indicate changes in how they related to the environment over the course of the program. Students recounted having autonomy to move within designated areas, seeking activities that offered sensory engagement and embodied learning, such as navigation, weeding, planting, and shelter building.

A teacher reflected on the importance of this connection:

You’ll see on my form, I’ve written, I’m very close to nature, I love it, and I love how this program is, which I think is important because humans are not from nature, we are part of nature, we, for millennia we’ve walked in it, worked with it, and we should still continue to do that.

This reflection speaks to the program’s underlying sustainability philosophy, re-establishing the understanding that humans are participants in, not separate from, ecological systems. Abram [50] describes the Western worldview as “deep-rooted and damaging” for its “tendency to view the sensuous earth as a subordinate space,” while Carson’s Silent Spring argued that human lives are interwoven within a “vast ecological community inherently worth preserving and protecting” [51]. The program encouraged students to experience this interconnectedness firsthand through receptivity, observation, and reflection.

Wandersee and Schussler [52] describe “plant blindness” as a modern condition of inattention to the living world, a symptom of disconnection that sustainability education seeks to address. By learning to slow down and observe, students began to develop dispositions essential for ecological citizenship, overcoming “nature blindness”, and cultivating humility and curiosity. One teacher noted:

I’ve noticed as we’ve gotten into the rhythm, they’ve also adapted to being out here. I notice them stop up here and have a look at the water levels and stuff and kind of slow down.

Participant observations illustrate how experiential, place-responsive learning cultivates ecological attunement. Facilitators intentionally fostered this slowness and observation. Through guided noticing and shared reflection, students began tracking insects, identifying animal tracks, and recognising changes in water levels and vegetation. Initially restless and fast-paced, participants gradually shifted toward stillness and attentiveness.

I remember in the very first week they were a little bit fast paced. It was hard for them to slow down and kind of just observe even the walk as we’re going to base camp.

By the later weeks, students were attuned to small ecological details:

[Student pauses] ‘What’s that bird call?’

Prum [53] reminds us that “knowledge without experience is never enough.” Direct encounters, such as watching a bowerbird’s behaviour or spotting a deer for the first time, merge cognitive understanding with emotional resonance. Such moments signalled students’ growing ecological literacy and increasing capacity to notice and interpret the living world; a transition from knowledge about nature to relationship with nature.

Quantitative DataValid and reliable measurement is a cornerstone of scientific or evidence-based research [54]. Robust quantitative research is based on using a standardised measurement through an instrument. For quantitative data to be effective and tell a story, implementation needs to be conducted in a systematic, rigorous and controlled manner [55]. Regrettably, this pilot encountered problems in this domain which will be outlined in the following section below.

As mentioned, the pilot research design employed both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods from students, teachers and facilitators. Martin and Czellar [28] EINS scale was chosen to capture participant’s nature connection and relationship with the natural world. This scale incorporated spatial circular metaphors to assess participants’ environmental identity and nature relatedness (see Figure 1).

There were a small number of participants who completed the EINS survey (N ≤ 10). This made it difficult for the pre- and post-test EINS scores to be matched. In part this was due to non-regular attendance by the participants, particularly on Week One of pre-test and the final week where the post-test occurred.

When selecting the EINS, the researchers had anticipated that its simplicity and visual style would be suitable for adolescent participants. However, this proved to be more difficult than imagined. Whilst data on participant disability or literacy skills was not collected, researchers observed students requesting help from program educators and school staff to read survey questions, to navigate the flow of text and images across the page, to hold attention on the survey, and refuse to complete the survey.

Participatory research carried out with children and adolescents has become a well-established component of the research landscape to gather data on their insights and perspectives [56]. When carrying out participatory research with special needs participants, scholars and practitioners must find creative ways to facilitate meaningful engagement with individuals and groups. Both WSU researchers and the GSP facilitators found harvesting reliable quantitative data from this population to be challenging.

To this end, the survey was administered as rigorously as possible within an ethical approach which responded to participant attention, willingness and capacity. Findings suggest that survey redesign for lower literacy levels, providing literacy and attentional support, and administering the survey at the beginning of a session may increase survey completion rates.

Our findings are consistent with global research on adolescent-focussed urban nature connectedness programs. A systematic review of 63 studies highlighted multiple benefits of connecting with nature particularly in promoting mental health, environmental stewardship and social inclusion [57]. Another systematic review of identified nature-based interventions in South Africa, Asia, the United Kingdom and North America reporting positive impacts on adolescents’ social skills, self-regulation, attention, motivation, independence, and problem-solving [58]. Similar results from studies of aligned programs in India [59], Canada [32], China and the UK [60] indicate a global trend of declining nature connectedness during adolescence.

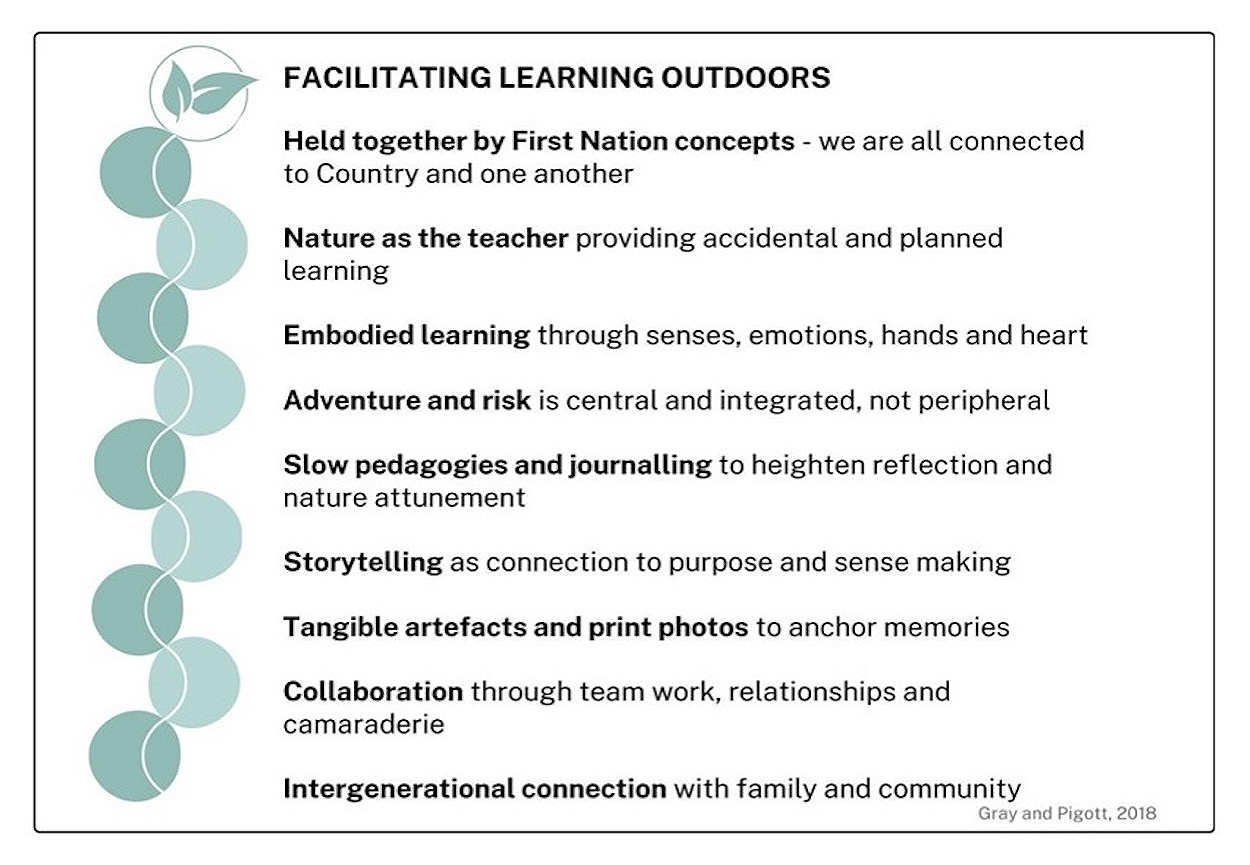

The GoP is heading into a second year of operation and can utilise these findings to enhance the program’s impact and acceptableness by amplifying and adjusting aspects of operation and delivery. Findings may be transferable to similar sustainability and environmental education interventions involving disadvantaged youth. Recommendations have been organised against design principles (see Figure 2) for facilitating outdoor learning that emerged from thirty years of reflective practice in the industry [10]. The following six provisional design principles are offered as analytically derived insights rather than prescriptive guidance, and are intended to inform future research and program design in comparable contexts.

Figure 2. A model for facilitating learning outdoors [10].

Figure 2. A model for facilitating learning outdoors [10].

Findings indicate that sustained engagement was strongest where learning was embedded within culturally grounded, intergenerational and relational contexts. Participants demonstrated heightened belonging, curiosity and respect for place when First Nations knowledge holders and trusted adult mentors were central to program delivery. This suggests that nature-based interventions for disadvantaged youth should prioritise relational continuity and embed cultural concepts throughout activities.

Held together by First Nations Concepts

In the GoP program, participants described Aboriginal Cultural sessions as meaningful opportunities to connect with Country and deepen respect for First Nations knowledge systems. The Alice Springs (Mpwarntwe) Education Declaration [61] calls for education that is grounded in the cultural knowledge and lived experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, developed in partnership with local communities. Both the Australian Curriculum [62] and NSW Syllabus [63] emphasise embedding Aboriginal histories and cultures into everyday learning through authentic, place-based experiences.

Intergenerational Connection

Strong intergenerational bonds were observed between GoP program students, educators, and program facilitators. Students frequently mentioned the humour, relational warmth, and technical expertise of staff. Sustainability education emphasises that the care and regeneration of the natural world are intergenerational responsibilities. When young people connect meaningfully with elders and mentors, they not only access cultural and ecological knowledge but also experience belonging within a continuum of care [64,65]. Research suggests that structured intergenerational experiences foster mutual learning, enhance wellbeing, and build resilience in both younger and older participants [66,67].

Design Principle 2: Place-Responsive Pedagogy Supports Ecological Attunement and Reflective CapacityFindings suggests that unstructured time for observation, slowness, and sensory engagement supported participants’ developing awareness of local ecosystems. Facilitated practices that foregrounded noticing, reflection, and responsiveness to seasonal and environmental conditions appeared to foster ecological literacy and a sense of place.

Nature as Teacher

Analysis of the project’s structure and delivery alongside student-reported experiences indicates a balance between serendipitous learning opportunities that respond to nature (e.g., weather conditions, animal movement, seasonal change) and intentionally planned skill and knowledge education (e.g., tool use, flora recognition, orienteering). This flexible approach enabled program staff to respond in real-time to ‘nature as teacher’ and utilise real-world examples to support skill development. Learning with, from, and through nature (or Country) has been an over sixty-thousand-year relationship for Aboriginal Australians, described as a reciprocal exchange “between me, the site, the site and me,” [68]. A systematic review of research of nature-specific outdoor learning suggests that academic and social-emotional outcome growth and attainment can be provided by natural outdoor settings. Pedagogical theorists invite educators to, “Get out of the way and let nature be the teacher,” , leaving space for serendipity and synchronicity with nature to guide outdoor learning sessions [10].

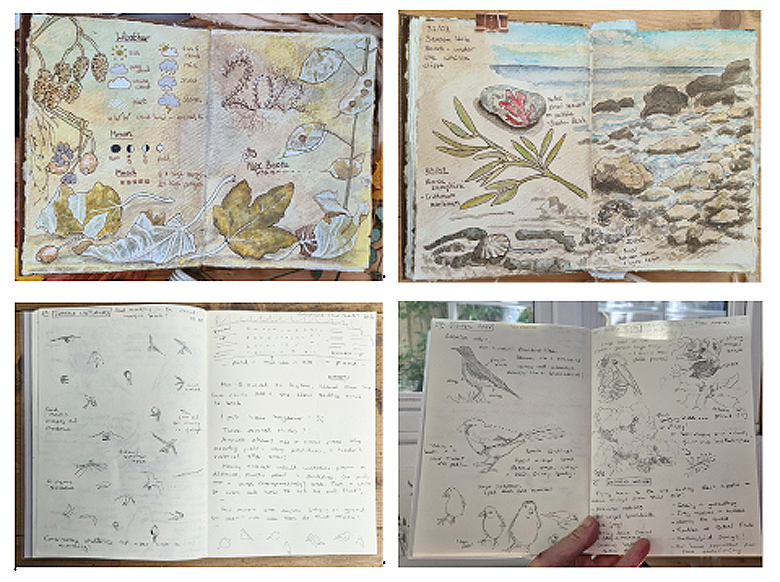

Slow Pedagogies and Reflective Nature Journalling

Although educators reported visible signs of nature attunement among students, many of these reflections were observational rather than directly expressed by students themselves. Structured opportunities for slow reflection can help young people articulate their learning, emotions, and sense of place, building an essential bridge between experience and understanding [69].

Slow pedagogies invite students to pause, observe, and make meaning at their own rhythm. Integrating journalling or sketching in self-chosen ‘sit spots’ fosters mindfulness and emotional regulation while deepening ecological noticing [10]. These journals, whether handwritten or multimodal, become living artefacts of inquiry by combining drawings, reflections, and audio-visual observations. Using mentor examples, such as shown in Figure 3, Boon [70] illustrated field journals, helps students see documentation as a creative and reflective practice [70].

Figure 3. Nature journals by Alex Boon [70] showing four sketches made in situ of natural materials, wildlife and landscapes, accompanied by observational notes.

Figure 3. Nature journals by Alex Boon [70] showing four sketches made in situ of natural materials, wildlife and landscapes, accompanied by observational notes.

Participants responded positively to activities involving authentic responsibility and managed risk, which appeared to support confidence, persistence, and executive functioning. These findings align with literature suggesting that appropriately scaffolded risk-taking can act as a catalyst for engagement and learning in outdoor contexts.

Adventure and Risk

The GoP program encouraged students to actively engaged in thrilling yet purposeful tasks, such as tool use, tree felling, whittling, and fire building. Facilitators intentionally framed these as opportunities for mastery, responsibility, and teamwork. Activities like navigating bush trails or working in unpredictable weather cultivated both practical competence and confidence. These authentic encounters with risk deepened students’ sense of agency and strengthened trust between peers and educators.

The social, emotional, and cognitive benefits of adventurous and risky play are well established [71]. Contemporary frameworks now encourage educators to view managed risk as essential for healthy development, wellbeing, and learning [72,73]. Such experiences challenge young people to assess, navigate, and adapt to uncertainty and develop skills foundational to both ecological literacy and resilience.

Design Principle 4: Participatory and Flexible Structures Enhance Relevance and EngagementThe program’s adaptive structure allowed facilitators to respond to participant interests, emergent questions, and group dynamics. Such flexibility appeared to support sustained engagement, particularly among students for whom rigid instructional formats had previously been unsuccessful.

Storytelling

While findings indicate that incidental storytelling naturally occurred through informal conversations and shared reflections, there was little evidence of deliberate use of story as a planned pedagogical tool. Intentionally embedding storytelling could strengthen intergenerational learning, deepen students’ sense of belonging, and enhance recall of ecological and cultural content.

Storytelling has long served as a core pedagogical tool in Indigenous cultures, enabling the transmission of traditional knowledges, values, and spiritual connections to Country [74]. Contemporary neuroscience supports this practice, showing that storytelling fosters social cohesion, empathy, and memory formation [75]. Stories act as a bridge between experience and meaning-making, helping learners situate themselves within wider ecological and cultural narratives [76].

Tangible Artefacts and Print Photos

Evidence from the program indicated minimal use of visual artefacts or digital documentation, largely due to school device policies. Introducing dedicated, program-managed technology could align with these policies while extending learning and reflection opportunities.

Though digital devices can sometimes distract from nature immersion [77] when used intentionally they can enhance observation, dialogue, and documentation of learning [78]. Capturing and reviewing photos or audio recordings enables students to anchor memories, celebrate contributions, and share discoveries. Tangible items transform fleeting experiences into lasting artefacts for reflection and discussion [79]. Examples in comparable programs include portable photo printers to allow these artefacts to be created in the field, fostering immediacy and ownership.

Design Principle 5: Collaborative Ecological Tasks Foster Social Connection and BelongingShared environmental work provided a meaningful context for collaboration across peer groups, supporting social confidence and mutual responsibility. These findings suggest that collective, place-based tasks may be particularly effective for addressing social isolation among disadvantaged adolescents.

Collaboration

Findings from GoP show that collaboration was a strong feature of the program. Students worked effectively with peers outside their friendship groups and developed trust with educators and facilitators. The program’s design balances autonomy with supportive scaffolding. This intentional design encouraged students who were typically hesitant or socially withdrawn to take risks, build confidence, and experience belonging through shared achievement. Collaborative experiences nurtured both social-emotional growth and a collective sense of stewardship toward place.

The Australian Curriculum: Personal and Social Capabilities highlights collaboration as a vital competency for developing empathy, perspective-taking, and collective problem-solving [63]. Outdoor, nature-specific programs are particularly effective for cultivating these skills, as they embed teamwork within authentic, embodied experiences.

Design Principle 6: Evaluation Methods Must Be Developmentally Responsive and Context-SensitiveThe challenges encountered in quantitative data collection highlight the need for evaluation approaches that align with participants’ cognitive, sensory, and emotional capacities. Mixed-method designs that privilege qualitative insight may be particularly appropriate in early-stage or exploratory interventions with complex cohorts.

Evaluation and Methodological Learning

The pilot project revealed how paper-based quantitative surveys can be fraught with difficulty. The quantitative section of the study gathered only a handful of reliably completed surveys. However, we are mindful of the inherent strengths of the quantitative component and will retain a mixed-method approach in future evaluations due to the methodical merits.

Conceptually and statistically, the results of a survey hinge upon how the sample responds to the instruments being used. The researchers are mindful that to improve the quality and impact of knowledge translation, it will require iterative revisions or adaptive approaches. Based on this premise, as the research moves forward in future iterations, a minor modification of the EINS instrument is needed to strengthen readability and coherence (see modification shown in Figure 4).

Appendix 1 outlines comprehensive revision of survey implementation practises and procedures including carefully selecting the timing of survey administration based on participants energy levels, providing literacy and attentional support from known and trusted adults, and offering alternative response pathways for students with additional learning needs.

The data collection methods moved away from a methodical number and ‘type’ of interview. This was an intentional decision to interviewing participants at appropriate times and in appropriate places. Rigid proposals for sample size and number of interviews often fail to consider the circumstances and people involved in the study [80]. Small sample sizes and limited interviews are critiqued from a positivist lens as they lack representation, weaken reliability, and increase the margins of error [81]. However, this research was trying to provide a deep and nuanced understanding of the participants’ experiences. That is to say, the project was primarily concerned with understanding participants’ experiences in a habitat restoration program. Given this framing, the research does not broadly generalise about youth habitat restoration programs. The program is a focused locality of a particular moment in time, which means there can be a lack of generalisability and replication of the study in other settings may produce different results [82].

The GoP program in Western Sydney provided wide-ranging benefits through immersive nature-based education for adolescents. The ten-week intervention showed increased confidence and social skills; a deeper attunement to nature and sense of place; and greater autonomy and executive function. Findings suggest the program increased teamwork, leadership skills, curiosity, receptiveness, observation, and knowledge of nature. The flexible and autonomous ethos of the program support these skills and behaviours to be cultivated and embedded.

This research contributes to a limited body of research around disadvantaged adolescents and nature disconnection, as well as the possible interventions that can be put in place. Additionally, the research develops a shared metalanguage between all stakeholders to assist with translating research into opportunities for future practices that have the potential to enhance the lives of young people. Further research and longitudinal studies may show whether programs like the GoP foster longstanding pro-environmental attitudes and social-emotional skills.

Ideas for Further Exploration in Survey Implementation

Explain the “Why”:

Clearly communicate the purpose of the survey and how their input can lead to positive changes or improvements in the class.

Connect to Student Interests:

Link survey topics to students’ existing interests or real-world applications to make the content more engaging.

Show How Feedback is Used:

Provide concrete examples of how past student feedback has been incorporated to make courses better.

Provide Choice & Alternatives

Offer Various Input Methods:

Don’t rely solely on written surveys; allow students to provide feedback through verbal discussions, turn-and-talk activities, or interactive digital tools.

Use Anonymous Options:

For students hesitant to speak up or provide their name, offer options for anonymous feedback to encourage their participation.

Incorporate Active Learning:

Design surveys as part of interactive activities, such as collaborative problem-solving, hands-on tasks, or short, focused Q&A sessions.

Build a Supportive Environment

Foster Community:

Create a classroom where students feel a sense of belonging and collaboration, making them more likely to contribute to discussions and feedback.

Build Relationships:

Get to know students individually, understand their unique perspectives, and build positive, trusting relationships to encourage them to share their thoughts.

Incorporate Movement & Breaks:

Regular short movement or brain breaks can help students stay focused and re-engage them throughout the class period.

Be Persistent & Patient

Encourage, Don’t Pressure:

Positively reinforce participation without putting undue pressure on students, especially those who may be shy or introverted.

Start Simple:

Begin with simple questions or smaller tasks to build confidence and gradually increase complexity as students become more comfortable with the process.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

Gray T, Pigott F. Reconnecting urban youth to nature in a place-based program for wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour: A qualitatively driven mixed-methods pilot study. J Sustain Res. 2026;8(1):e260009. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20260009.

Copyright © Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions